As an Amazon Associate, Ultimatetennisgear earns from qualifying purchases. This post contains links which generate commission at no cost to you if you purchase through the link. Find out more about affiliate links here.

On paper, the modern professional game has it all – glamour, glitz, power and physicality… all under the watchful gaze of statisticians, analysts and the usual bunch of marketers and PR types. Watch any modern tournament and your eyes will be seduced by the show, while your body trembles in response to the modern game’s speed. What kind of romantic fool could possibly look back in time through rose tinted spectacles…?

There’s a certain gladiatorial purity to a game of tennis: two players whacking a ball about until one wins and one loses. No coaching, no complicated rules, no handicaps…everything is laid bare for all to see. A tennis match, on its own, is a sufficient magnet for the keen tennis player – if you play the game, there is much subtlety to take in, like the natural ebb and flow of the professional game that so accurately mirrors the trials and tribulations of the amateur game.

Evolving to survive

To become the global sensation it is today, tennis had to evolve, and nobody should hold that against it: squash and racquetball failed in this very basic task, and now have their glory days firmly in the rear view mirror. Ever been in a gym that looks suspiciously like an old squash or racquetball court?

The first part of the evolution came as pro tennis started a long journey from sport to entertainment. Rather ordinary tournament locations were spiced up for the TV audience, prize pots increased and the stars of the game became media personalities, with a presence that often didn’t correlate to how well they actually played…remember Anna Kournikova?

In parallel with the increased media profile of players came the big money endorsements – top players can earn serious money from sponsors, selling their soles for a wide range of products, often with no link to tennis. There’s the slight issue of the endorsement of racquets that they don’t actually play with, but that’s another story.

More about the marketing/media later. Let’s pivot to the other part of tennis’ evolution: the equipment and science. Racquet and string technology has taken the unlikely love child of cows and trees, and turned it into the the graphite and poly marvels of today. The players are true athletes, with expert nutrition, fitness and psychological guidance. The game is faster, harder and more technical – every aspect of modern tennis would terrify a player from the 1970s.

So here we are – a modern game that, from the point of view of statistics, eclipses all that has come before. The ATP and WTA are highly professional, tournaments are highly polished and TV coverage ensures that we can all get our fix on demand.

What’s not to love?

Don’t get me wrong, the modern game is a wonderful thing – pull up footage from the 1960s and you’ll think the video is playing at the wrong speed. The audiences seem disengaged, apart from the occasional outbreak of polite clapping, and even the players seem only mildly happy with victory. However, there are issues with the modern game and, like any elephant, they are unlikely to leave the room unaided.

The concentration of money at the top of the game has made it harder for talented players to break into the top levels: you’re up against players with a huge entourage of professionals, from coaches to personal stringers. This plays against one of the fundamentals of sport: unpredictability. What’s the point of watching if one outcome is overwhelmingly likely? We remember the giant killers, the unexpected runs, the emotion of the minnow defeating the shark. The modern game has become more predictable – just look at the number of titles won by the big three in the last 16 years.

Technology and statistical analysis have come together to create a modern recipe for winning – the successful serve volleyer is long gone, the quirky style has been corrected and the melt downs have largely been cured. Instead, there is a very narrow range of styles at play on the tour, with each tactic and move planned by computer beforehand rather than improvised on the run.

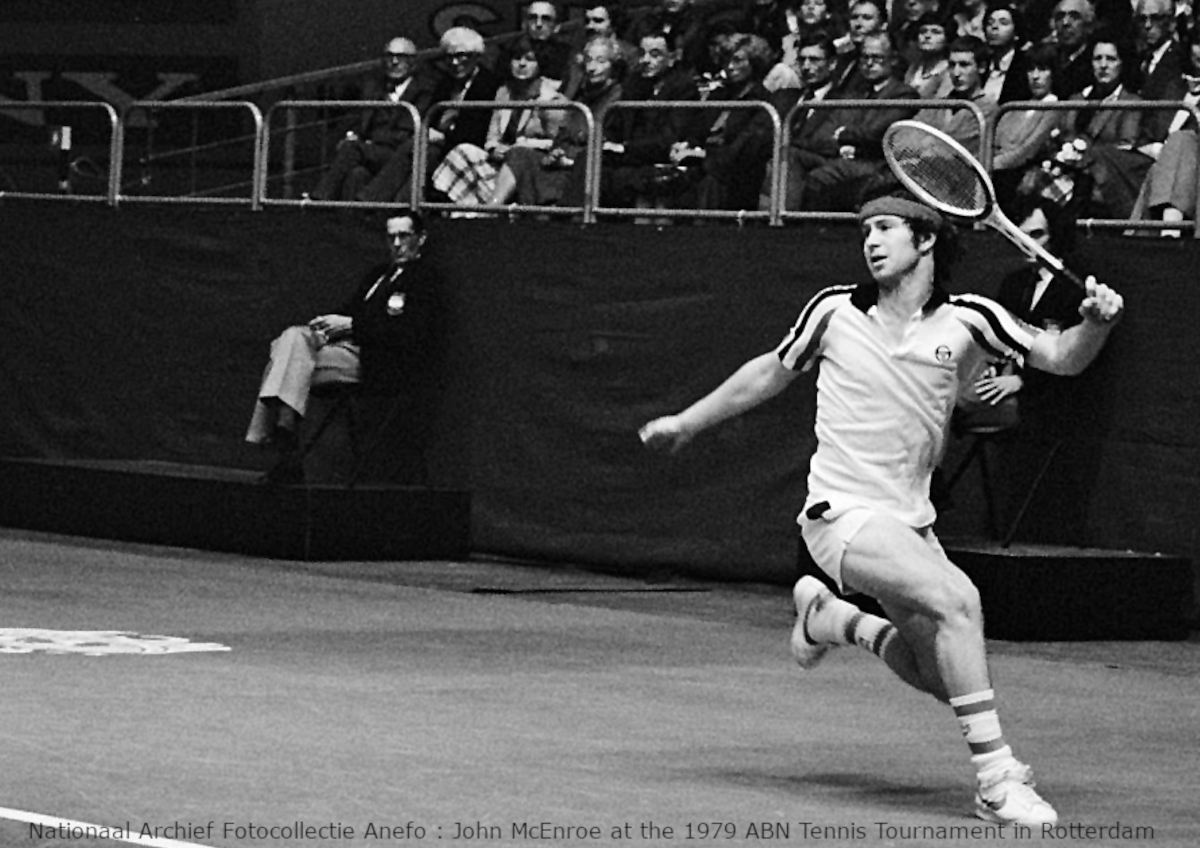

Finally, the relentless march of professionalism has claimed its first scalp: the very personalities of the players themselves. I’m not suggesting that we need the childish and seemingly contrived antics of McEnroe, but the current crop of post match interviews could cure insomnia. To be at the top of the game, you have to start young and pretty much sacrifice your life for the game. In the interviews it shows. Add pressure from lucrative sponsorship deals to be inoffensive and the now constant social media nonsense, and you feel like you’re talking with a PR officer rather than a passionate player. Its a sad irony that, the bigger the media profile, the less personality we seem to get.

What About Nick?

Australian Nick Kyrgios seems to be the only genuine nutter on the pro circuit. Seemingly one penguin short of a full zoo, the Australian regularly grabs the headlines for his antics, shots and bizarre interviews. Unfortunately, he’s pretty much the only one, and you can’t condone that much racquet smashing from anybody. Put simply, the pro tour’s desire to sanitize might have turned round and slapped itself in the proverbial buttocks.

Heroes and Villains

Traditionally, if you wanted to be bored to death, there was a sport made especially for you…. golf. The true sleeping pill of the masses, it soothes and relaxes in equal measure with its soundtrack of whisped commentary and polite ‘Ooohs’ and ‘Aaaaahs’. Perhaps, in retrospect, we need to add a touch of McEnroe back to our own sport- read anything by Shakespeare and you quickly realize that love is nothing without hate, and a hero is nothing without a villain.

If all this talk has got you nostalgic for the past, then check out these tennis books:

The History of Tennis by Richard Evans takes readers right back to the beginnings of the sport, and charts its progress to the modern day game that we know today. It covers key events and players, and brings it all to life with wonderful photographs.

US Open: 50 Years of Championship Tennis by the United States Tennis Association is a wonderful look back at the history of one of the world’s great tournaments. A wealth of information and stories about the competition and players is matched by wonderful photographs that capture the passion of the event.

Wimbledon – The Official History charts 150 years of competition, from the humble beginnings as an effort to raise money to fix a broken lawn mower to the strawberries and cream fueled celebration of the game that we love today.